Historic Graveyard

As the first public cemetery in Richmond, our inhabitants represent a core of early settlers to the colony of Virginia and the first citizens of a new country. Many were born in England, Scotland, and Ireland; France and Spain are also represented. Heroes of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 rest here as do a great many children and infants. Some have incredible biographies; some will be unknown to us forever.

Graveyard Tour

with audio

These stones have a story to tell.

Together they are part of the story of early Virginia, Richmond, and the nation, and their stories— be they celebrated or long forgotten— flesh out the story of life (and death) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In order to hear their stories, we must preserve their history.

Looking for a private or specialized tour?

A Cemetery Story

One woman with a fascinating and sad story is Elizabeth Arnold Poe, often called Eliza. She died in Richmond in December 1811, leaving behind three small children. The middle child, Edgar, was taken in by the Allan family, hence the moniker Edgar Allan Poe. This video includes her story, and her memorial stone here at St. John’s. The church appears at minute 11:20.

An obelisk on the east side of the church.

Cemetery Preservation

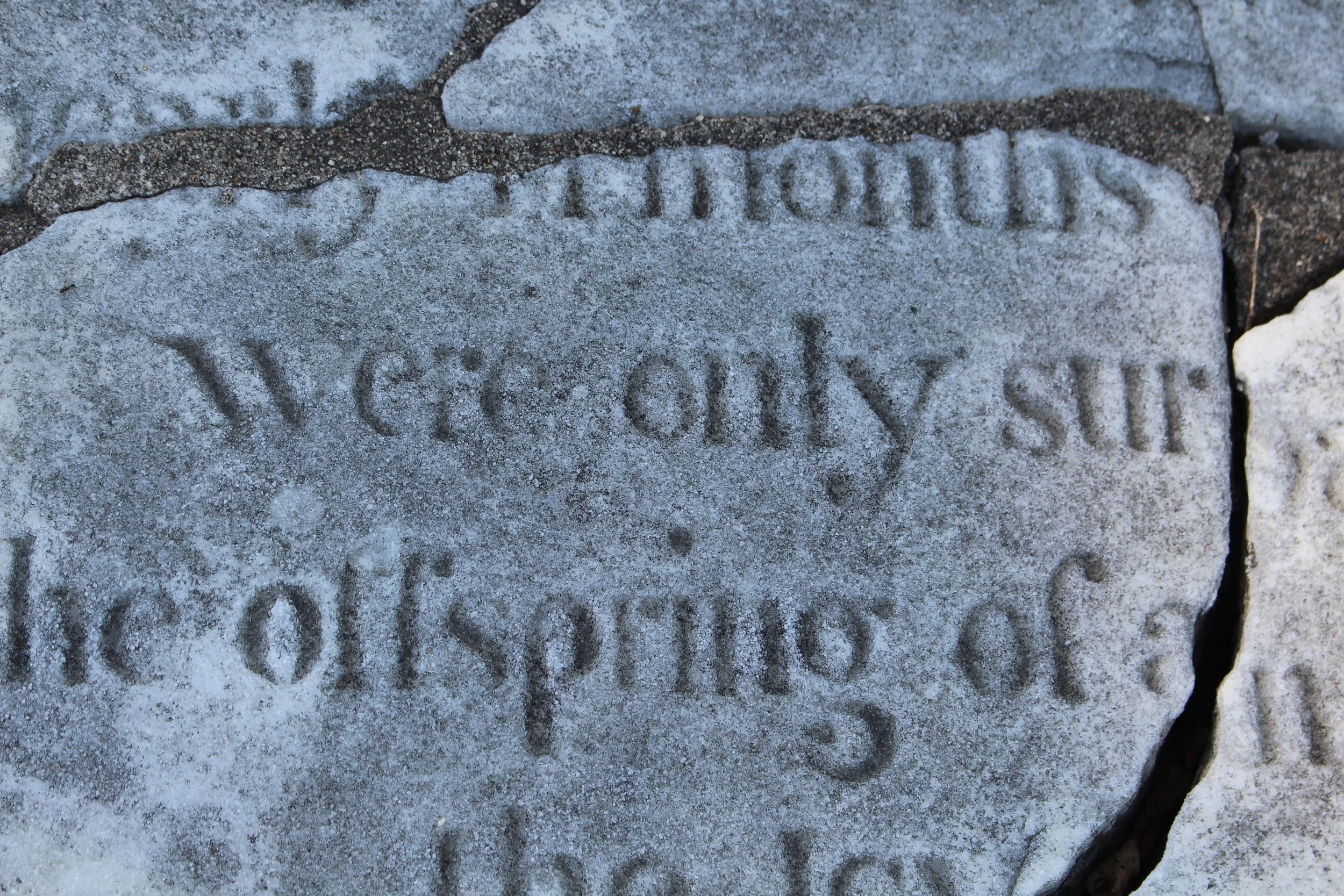

About 400 gravestones remain above ground at St. John’s. Many of these are weathered, worn and in need of repair. Conservationists estimate that 117 are in critical condition; another 107 are considered second level priority. Acid rain, pollution, and bird droppings cause continuous deterioration to fragile stone materials.

Dr. Brian Whiting maneuvers the radar over a section of the cemetery.

Ground Penetrating Radar

We have started several important projects in order to preserve and learn more about our graveyard. In 2018 we undertook an exciting GPR (Ground Penetrating Radar) Project to try to decipher a little more of what lies underneath our feet. As a result of this research we now believe there could be up to 3000 souls buried at St. John’s. We will continue to map more sections of the graveyard as time and money permits.

Adopt-A-Grave

Join us in our mission to preserve these valuable grave markers and assess Richmond’s first cemetery. Our Adopt-A-Grave program is a way to help with cemetery restoration. Gravestone repairs coupled with research provided by the church archives, our staff and volunteers, allow us to decipher more clues to this oldest resting place in Richmond.

Graveyard Nerd T-Shirts

Requiescat in pace

History of the Cemetery

Constructed in the 1740s, St. John’s Church was built on what was then known as Indian Town Hill (now Church Hill) on an acre of land donated by William Byrd II of Westover Plantation. Needs of the vestry resulted in several expansions of the original 60-by-25 foot building: a 40-by-40 foot addition in 1772, a north addition in the 1830s, and a south addition in 1905.

At some early point in its history, the church grounds began to serve as a burial location for the congregants. In 1799 Richmond municipal officials purchased two lots bordering Broad Street and adjacent the St. John’s property to provide a public cemetery. The city also paid for a brick wall to enclose the entire area bordered by Broad, Grace, Twenty-forth, and Twenty-fifth Streets. By about 1820, the “whole square had now been filled with graves,” and church officials raised concerns about further burials. St. John’s was the only public cemetery until Richmond opened Shockoe Cemetery in 1822.

The exact number of interments at St. John’s is (and likely always will be) unknown. Prior to our Grave Penetrating Radar Project, the number of burials was estimated at about 1,400; now we believe that it’s closer to 3,400. Several factors hinder burial quantification and identification. Over its nearly three-century history, the church’s fortunes have fluctuated—conditions declined in the 1830s such that some families moved the remains of their loved ones to other cemeteries. Many if not most of the original markers are no longer extant, and those that do exist are often difficult to read due to weathering, the impact of military operations, vandalism, and other factors. In many cases, the location of a marker does not represent the actual burial site. In addition, the various expansions of the church and construction of subordinate buildings referred to above have been built over existing grave sites.